The City and The City Theoretical Reading

Ecocriticism in China Mieville’s The City and The City

“Ecocriticism is a study of culture and cultural products (art works, writings, scientific theories, etc.) that is in some way connected with the human relationship to the natural world” (Dean 1). The natural world is the equivalent to the physical environment, which consists of the biotic factors (such as animals, plants and bacteria) and abiotic factors (such as soil, temperature, sunlight and water) that form our surroundings. China Mieville’s The City and The City explores the relationship between the twin cities of Beszel and Ul Qoma and the effect they have on the physical environment of the individual cities and also on its citizens. This makes Mieville's novel suitable for an Eco-criticism reading.

Cornucopia and the theme of denial

The cornucopian position is a term for people who believe that “…capitalist economies will generate solutions for environmental problems as they arise” (Garrard 19). For example, people of the cornucopian position argue that the scarcity of natural resources will lead to “capitalist entrepreneurs to search for substitute sources, processes or materials” (Garrard 19) to replace the scarce resource. Cornucopians also believe in “…environmental ‘scare-mongering’, citing inaccurate projections of global warming and worldwide famine made by some ecologists in the 1970s” (Garrard 20). Essentially, cornucopians deny the magnitude of particular environmental issues (often caused or intensified by the modern, capitalist culture) and blindly put their faith in aspects of capitalist economies, such as the belief there is an “endless cornucopia of wealth, growth and commodity production” (Garrard 20), to solve environmental issues rather than taking action themselves- such as a reduction in the consumption of natural resources. This ecological position has a parallel with the actions of the citizens found within the two cities of Beszel and Ul Qoma in China Mieville’s novel.

The cornucopian viewpoint that the scarcity of resources will lead to economic growth that will solve the environmental issue can be viewed as being criticized in a description of Beszel’s river industry. It is noted how “As the river industry of Beszel had slowed, Ul Qoma’s business picked up” (Miéville 54) and how as a result “the once-collapsing Ul Qoma rookeries…were renovated” (Miéville 54). In contrast, Beszel’s dead river industry is described by comparing to the now unused docks as “iron skeletons” (Miéville 54). The depiction of Beszel’s devastated and unused river and how it contrasts with Ul Qoma’s renovated lands highlights the depletion of natural resources from the area in order to produce economic growth in Ul Qoma. Therefore, this criticises the cornucopian idea that scarcity of resources will lead to economic growth that will solve the environmental issue, because whilst economic growth in Ul Qoma has occurred, the river, its industry and its surrounding area remain ruined and depleted in Beszel, which suggests the environmental issue has not been solved by economy growth in Ul Qoma. However, citizens of Ul Qoma will “unsee” the river in Beszel, and therefore will essentially deny this environmental issue. This symbolises how cornucopians deny the magnitude of environmental issues their society has caused and embrace aspects of capitalist economies instead.

The cornucopian tendency to put blindly put faith in capitalist economies to sort environmental problems (rather than taking action themselves) is further highlighted through the concept of Breach in the novel. In The City and The City, Breach is an organization that keeps the separation between the two cities in place and also takes action when people cross from one city to another. Therefore, Breach can be viewed as an entity that is relied on to sort issues relating to the physical environment. In addition, characters in the novel talk about how they rely solely on Breach, and therefore do not take action themselves when incidents involving breaching occurs. For example, in the oversight committee about Mahalia Geary’s murder, one person comments how “Breach is and I say it again alien power, and we hand over our sovereignty to it at our peril. We’ve simply washed our hands of any difficult situations and handed them to a- apologies if I offend, but a shadow over which we have no control. Simply to make our lives easier” (Miéville 78), which highlights how the people of Beszel and Ul Qoma do not take direct action themselves concerning issues of the physical environment and instead, put their faith in what they describe as a “shadow”. This depiction of the citizens of both cities choosing to blindly put their faith in "...a shadow over which we have no control" to deal with difficiult situations regarding their environment can be viewed as a critique of the cornucopian ecological position and how cornucopians blindly put their faith in capitalist economies- instead of taking action themselves.

Animal Crossbreeding

The exploration of man’s relationship with other species (both plant and animal) has been a recurring theme throughout literature for hundreds of years. For instance, in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, the play explores the idea of cross-breeding plant species when the characters of Pertida and Polixenes’ discuss the latter’s cross-bred flowers. Pertida refers to them as “nature’s bastards” whilst Polixenes describes it as an “art/Which does mend nature, change it rather, but/The art itself is nature”. Whilst Polixenes thinks of crossbreeding as an “art” that fixes nature, Pertida refers to the cross-bred flowers as “nature’s bastards” which suggests she thinks that altering or mending nature to suit the needs of humans is an unnatural and a perhaps unethical process. The idea that crossbreeding animal or plant species for humanity's gain is unnatural is an idea that is also suggested in The City and The City through the metaphor of the two cities.

Throughout the novel, the description of the two cities juxtaposes with one another. Aspects of the two cities’ culture, such as clothing, architecture and politics, contrast with the opposite city- for instance, the cities supported opposite sides in World War II. Another example of this difference in culture and politics is seen when Tyador notes how “There are no legal socialist parties, fascist parties, religious parties in Ul Qoma” (Miéville 196) whereas it is the opposite in Beszel. Another example of the juxtaposition between the cities is highlighted through the interrogation techniques used by the inspectors of each city. Whilst Tyador of Beszel interviews and interrogates suspects without resorting to violence, Inspector Dhatt of Ul Qoma uses violence when questioning unificationists and is described as having “cuffed the man nearest him” (Miéville 195) and then as having “slapped his friend yet again” (Miéville 196). This use of juxtaposition highlights the contrast between the cultures of Ul Qoma and Beszel.

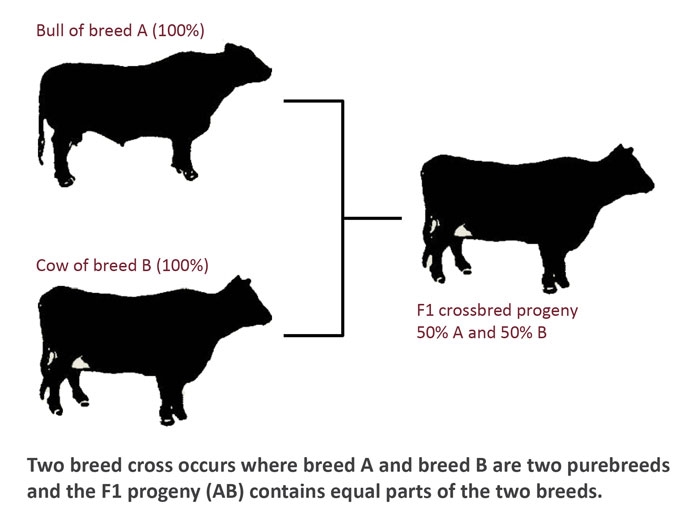

However, despite the different in culture, throughout the novel we see activists and unificationists who want to see the two contrasting cities of Beszel and Ul Qoma to be united as one and merged into one city. A possible merger between the two cities is compared to animal crossbreeding by Inspector Dhatt, who says “Unity is strength my Ul Qoman arse. I know they say animal crossbreeding makes animals stronger, but what if we inherit, shit, Ul Qoman sense of timing and Besz optimism?” (Miéville 193). The fact the two cities contrast heavily in numerous aspects of their cultures suggests a possible merger would be an unnatural and potentially disastrous process. This is further proven later in the novel, when the city of Beszel breaches into Ul Qoma causing the two cities to essentially become one, which leads to riots and criminal behaviour in the streets of both cities. Therefore, the comparison of an unnatural and potentially dangerous merger of two contrasting cities to animal crossbreeding, suggests animal crossbreeding for human needs and gain is also an unnatural and potentially harmful process.

The Destruction and Freedom of Nature

As discussed before, the novel juxtaposes the cultures of the two cities, but consistently highlights how the environment is being damaged in both. An example of environmental damage in Beszel was highlighted through the depiction of its dead river industry. An example of environmental damage in Ul Qoma is seen through the park where the archaeological dig is located and how it’s described as being surrounded by the growth of the city. It is noted how “In places the park and the site itself were edged right up to its rubble and boscage by the rear of its buildings” (Miéville 174). It’s also highlighted how “The Bol Ye’an dig had about a year before the exigencies of city growth would smother it…and with official expressions of regret and necessity, another (Beszel punctuated) block of offices would rise in Ul Qoma” (Miéville 174). Because the park and archaeological dig can be considered an area of natural resources (such as soil), the imagery of the city surrounding and smothering it highlights how human activity is slowly depleting the world of natural resources to sustain modern life. The fact that the novel highlights environmental damage in both cities suggests that no matter what culture or city you are a part of, damage to the natural world through humanity’s actions will always inevitably happen, which paints a negative depiction of the natural world in modern times.

However, whilst the novel highlights the destruction of nature across different cultures, the novel can also be viewed as highlighting the freedom of nature, and how nature is free of the boundaries that restrict mankind. At several points in the novel, it highlights how animals and other natural factors can breach into the other city without consequence, which is something humans are unable to do. For example, it is noted how “…Ul Qoman’s dog runs up and sniffs a Besz passerby” (Miéville 80); how Tyador, as a child, used to throw “local lizards” through crosshatched places into the other city (Miéville 86); how “Pigeons, mice, wolves, bats live in both cities, are crosshatched animals” (Miéville 112) and finally, how Tyador “…watched the river, that was here the Shach-Ein” (Miéville 172). This highlights how biotic and abiotic factors of the natural world, such as rivers and animals, are free of boundaries that constrict human beings. Therefore, The City and The City can be viewed as a positive depiction of the natural world, one that breaks free of the political, cultural and geographical restrictions that constrict and separate the human citizens of Beszel and Ul Qoma.

Works Cited

Garrard, Greg. Ecocriticism. Taylor & Francis, 2011. Print.

Miéville, China. The City & The City. London, Macmillan, 2011. Print.

"What is Eco-Criticism?" Thomas K. Dean, Association for the study of Literature & Environment. n,d. Web. 10 May 2014.

Alexander Brock