Sophie Seita

Enclosing ‘Rape’ in Peter Larkin’s ‘Five Plantation Clumps Near Twopence Spring’

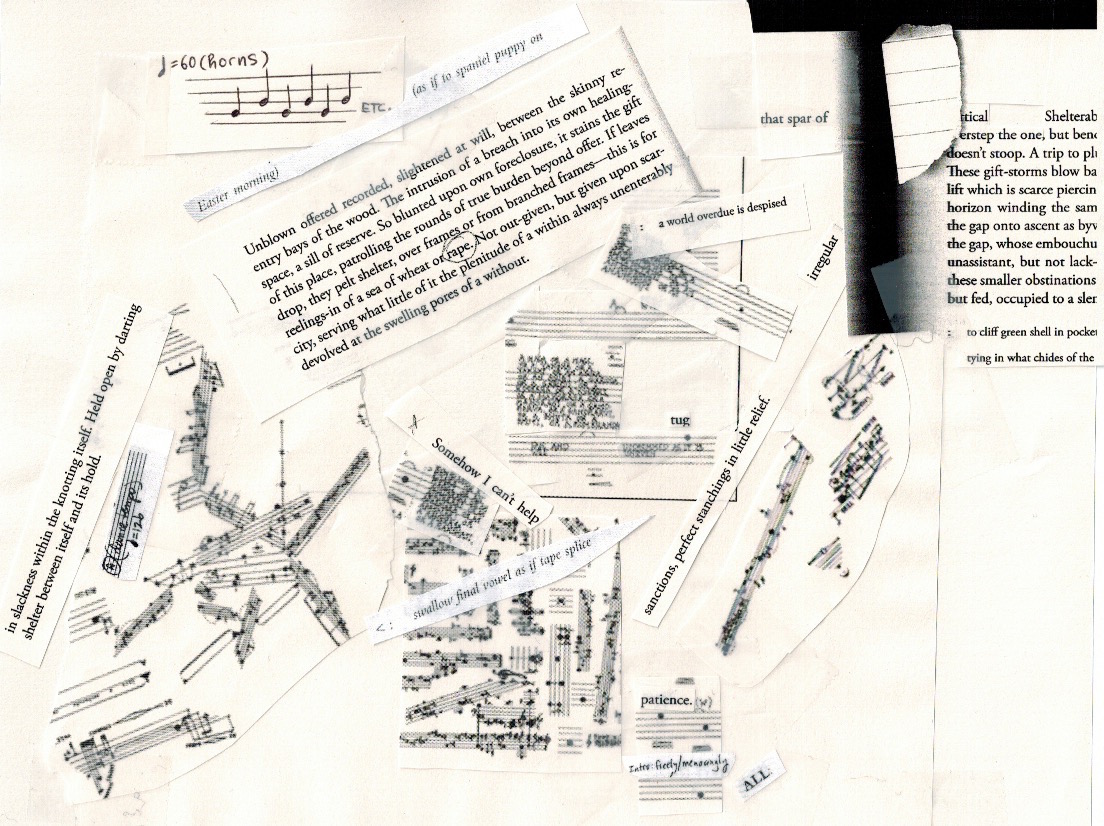

‘Score for Voice and a Metronome: with John Cage and Sylvano Bussotti’

Circling, eyeing, fixing on: a word, a metaphoric situation, from a different context, but pressing and topical. How can we acknowledge that contemporary discourses and activist discussions in our poetry communities influence scholarly attention—hopefully to the benefit of the text at hand?

The ‘sea of wheat or rape’ is plants, biblical (in its bountiful promise), Van Gogh; yet, this common (even dead) metaphoric displacement of the little for what the eye sees as bigger and connected has me stuck on ‘rape’, pondering the connection of the homonym with its other senses as a way to ‘measure out the land’, ‘rope off’ territory, as possession, and crucially, as violent seizure of land and another’s body (typically, a woman’s). Larkin’s poem anticipates the word’s aggression in ‘the intrusion of a breach into its own healing space’ and with ‘unenterable’, ‘pelt’, ‘stains’, ‘blunted’ and ‘slightened’. How can we introduce questions about gendered violence and gendered perceptions inside critiques of humankind’s relation with nature, so that they become visible, and do some work for us?

Larkin’s text knows the ‘predicament’ of nature’s impossible innocence, of an always-already transgressed corruption and incorporation into commercial and exploitative patterns. It knows about the history of inappropriate metaphoric mapping. It is precisely because of the discourses around innocence and corruption inside nature that have historically been mapped onto female bodies and lives that it would feel like carelessness on my part not to mention my noticing the metaphoric setting of this stanza. And Larkin’s poetry allows precisely such questions of necessity and urgency—about what we should pay attention to.

Based on an ethics of relation, a ‘scarcity of relation’ or ‘ontology of scarcity’, Larkin’s poetic nature-scenes are never idyllic, nor easy; description is always interrogated for its adequacy, its reach.[i] The text’s density and insistent qualifications, the modifications of the smallest grammatical unit, are attempts to show awareness of the problematic engagement (even if remotely or especially when) with a pastoral tradition.

The experience of reading Larkin’s work is also one of breaches, of affliction, of property (see this stanza’s use of ‘foreclosure’), possession, war, of microscopic terrors and (en)tanglements, impossible recuperation, but also a horizon of actuality, a gift of/as scarcity. Trees, parts of plants, are under assault, just as much as they are under inspection; there is an imperfection as well as an ethical dilemma for the writer and reader, of where to position yourself in relation to the object of description, to make yourself answerable: ‘An answerable innovation is one that respects the scarcity of fundamental resource opportunities out of which cultures can be remade and does not squander them in some accelerated hyperconsumption of the other’.[ii]

How can we investigate cultural-literary material especially when it is seemingly so en passant as that little ‘rape’, the word itself part of the tradition of poetry and the gendered narratives of the pastoral (both anti- and proper) in which this poetry intervenes? Rape metaphors are used frequently in environmental discourse: the rape of the land, the rape of nature—which is maternal, which is female (of course). To this we can add metaphors of wildness/wilderness, like ‘virgin forest’ or ‘penetrating the wilderness’, the former containing a repulsive religious–moral condescension, the latter an uncomfortable penile and colonial twinge. ‘Our’ language for nature is always burdened with gendered and racist imagery.

The exploitation of nature—both mourned and described with a scientifically-minded sensibility in this stanza—is thus unavoidably feminised (or could it be avoided?). Metaphors mirror and structure our realities. Rape is a reality; also in leftist poetry circles. There are patriarchal dualisms, hierarchies, and objectifications that need to be highlighted and understood. So, looking at the implications of, and persistence of certain metaphors, as Rachel Blau DuPlessis rightly points out, feminist readings ‘need not lose formal specificity nor overlook the saturated, pleasurable textiness of poetic texts’.[iii]

Rape, the radish, the root. Also ‘to rasp, scrape, grate. […] to scratch violently’.[iv] ‘Stain[ing] the gift of this place’, the word ‘rape’ leaves a stain on the page; impossible to scratch out. This gloss has refracted itself into a reflection of what we can say and cannot say in such a generic space about a small portion of a text. This gloss is itself written in the margin, like feminism, like a doodle, an un-singable score, an off-hand thought, which still persists, and must. As notes to ourselves, we often write in the margins to remind ourselves of something, to hold ourselves accountable.

Initially, the form of the score for voice appealed to me because of Larkin’s poetry’s sound-play, assonance, alliteration, and other repetition that make for good speaking or singing, and because graphic notation in music seems clearly related to the abundance of marginalia. It would be easy to make such a score with Larkin’s words sound beautiful, because the words often are beautiful, but what can be gained from such a musical match? There is another kind of beauty in the thinking-through and complex juxtaposition of a number of possible rhythmical orientations.

Graphic scores demand creative responsibility from the performer; they ask you to make connections; they are not written out plainly; they’re not easily digestible, nor even legible. But does the score need sound as empirical authentication or justification? What if it was just radically and pleasurably impractical? Graphic notation creates a sensual overload, similar to that encountered by Larkin’s poetry.

If there is a horizon, which can be glimpsed in and through poetry, a visible invisibility, then the uncomfortable elements that allow for such horizons must be under scrutiny also. A gendered response like mine both is and isn’t marginal; certain choices have been the meat of poetic production and consumption, i.e. that which is transformed, which is commodified, which is made edible as a result of violence.

There is a tension in Larkin’s poem between depicting a form of experienced (projected) violence and the right language to describe it, a language that puts something at stake.

How this transferred homonym burdens the poor, innocent rape plant! One can move far off a text and still remain intimately caught up with it. That this poem still and nevertheless and of course and at the same time also engages with Larkin’s impressive arboreal phenomenological poetics is out of the question.

Lastly, what such a short foray really reveals is how much we can or should care about these questions. And if there is one thing that reading Larkin and difficult work like his has repeatedly revealed to me, it is the value of and care for minute meanings and disturbances and doggedly knotted phenomena that require attention, inside the text and beyond it.

A gloss on my gloss:

I wrote this essay at the beginning of 2015 after a summer and winter of various rape allegations, druggings, stories of sexual harassment, and other incidents of misogyny in the variously interlinked New York, London, and Bay Area poetry worlds. At the time of Amy Cutler’s commission, I found it difficult to read or write anything that wasn’t somehow inflected by this context. Glossing without an explicitly feminist commitment suddenly seemed perverse to me. ‘A world overdue is despised’; it calls for re-scoring. For a feminist voice. I’m grateful to Amy for the invitation and the freedom to experiment with my response in this way.

Collage sources:

John Cage, Solo for Voice No.12, in SONG BOOKS (1970).

Sylvano Bussotti: La Passion selon Sade (1966) and Manifesto per Kalinowski (1959).

Michael Ives, ‘Ye Shall Receive (An Elegy to the Near 90s)’, Chain, 9 (Summer 2002), pp. 125-135.

Peter Larkin, Lessways Least Scarce Among: Poems 2002-2009 (Bristol: Shearsman, 2012), pp. 16-17.

[i] Peter Larkin, Wordsworth and Coleridge: Promising Losses (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 2-3.

[ii] Peter Larkin, ‘Innovation Contra Acceleration’, boundary 2, 26.1 (Spring 1999), 169-74 (p.173).

[iii] Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Blue Studios: Poetry and Its Cultural Work (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), p. 122.

[iv] ‘rape, v.3.’, OED Online (Oxford University Press, September 2014), online [accessed 16 November 2014].