Irish Migration to Liverpool and Lancashire in the Nineteenth Century

Laura Kelly

I'm bidding you a long farewell, my Mary, kind and true

But I'll not forget you, darling, in the land I'm going to.

They say there's bread and work for all, and the sun shines always there

But I'll ne'er forget old Ireland, were it fifty times as fair.

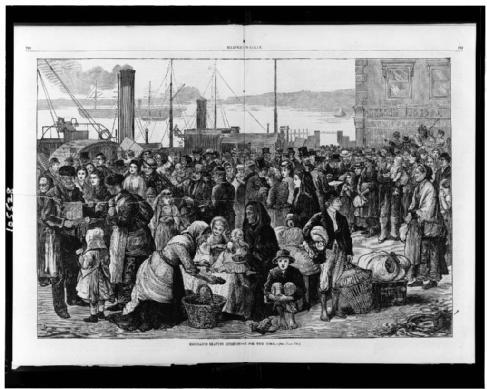

Irish emigration to Britain developed slowly up until the late 1840s, when, as a result of the Great Famine (1846-52), there was a huge acceleration in numbers of Irish men, women and children leaving the country for better lives overseas in Britain, North America and Australia. The Famine had a devastating effect on the Irish population with 1 million dying from starvation and disease and, by 1855, a further 1.5 million had been forced to emigrate. Attracted by the prospect of work and relief through the English Poor Law system, considerable numbers travelled to the major towns and cities of the northwest of England. Lancashire, and in particular, the port of Liverpool, absorbed the greatest number of Irish emigrants because it was the primary destination for those leaving Ireland. Although migrants often arrived in Liverpool with the aim of continuing their journey to North America or Australia, many only had the resources for the first part of their journey. Others exhausted their fares for passage to America while waiting to depart, became too ill to travel, or fell victim to criminals who preyed upon their inexperience and exhaustion. And these became trapped in Liverpool and the Lancashire region. According to census returns for 1851, the Irish-born population in Lancashire, which had almost doubled in the previous decade to reach over 191,000, represented 10 per cent of the county’s inhabitants. In Liverpool, the Irish-born population, boosted by Famine migration, similarly rose from 17.3 per cent of the total population in 1841 to 22.3 per cent in 1851. In 1871, despite a decrease in Irish emigration, Irish migrants still represented over 15 per cent of the population of Liverpool. Between 1850 and 1913 it is estimated that more than 4.5 million Irish men and women had emigrated.

Conditions on the ships taking Irish emigrants overseas were perilous and mortality rates were high. According to Robert Scally, ‘on most ships, poor provisions, physical environment and diseases related to the journey assured that remaining susceptibilities of old age, illness or youth were again tested’ (see ‘The hospital and cemetary of Ireland’). Passengers who started their voyage in a healthy condition were often met with dismay by the authorities upon their arrival at the port in Liverpool, while others did not reach their destination alive. In 1848, the S.S. Londonderry, a steamship sailing from Sligo to Liverpool, encountered stormy weather conditions. The 150 steerage passengers were trapped in tight conditions in the hold below which measured just 20 feet long with six and a half feet headroom. 72 passengers perished in the disaster.

Irish migrants disembarking at Liverpool during the Famine years were observed to have been in a state of extreme distress, destitution and exhaustion, and press reports from the period expressed concern about the tax burden of Famine migrants on local ratepayers, the impact on the city’s health and the suffering of the migrants themselves. For example, the Liverpool Mercury sympathetically reported in 1847:

The fact is; that in the cold and gloom of a severe winter, thousands of hungry and half naked wretches are wandering about, not knowing how to obtain a sufficiency of the commonest food nor shelter from the piercing cold. The numbers of starving Irish men, women and children—daily landed on our quays is appalling; and the Parish of Liverpool has at present, the painful and most costly task to encounter, of keeping them alive, if possible…

The Lancet medical journal also referred to the poor health of Irish emigrants. One particularly harrowing account described the migrants who arrived in Liverpool in the first six months of 1847 as:

80,000… located themselves in dog-kennels and cellars, and remained to glut the labour market and propagate a wretched mode of life. In this unhappy year, 60,000 persons were attacked with fever, and 40,000 with dysentery.

As the report illustrates, Irish migrants were generally compelled to stay in overcrowded housing in districts lacking sanitation which were prone to outbreaks of epidemic diseases.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the migration patterns of Irish to Lancashire were varied and included young families, single men and women of varying ages, who were attracted by work in the mills. From the 1860s, however, the typical Irish migrant to Lancashire was young and single; these individuals lacked family support networks and were thus therefore more susceptible to institutionalisation in times of unemployment. At times of peak employment, the Irish were recognised as being a crucial source of labour for the local economy in the north-west of England. Most Irish migrants worked in the worst-paid, lower classes of employment, surviving on a typical poor Irish diet comprised of potatoes, buttermilk and occasionally herring or bacon. In 1870, 82 per cent of Irish migrants in Liverpool were listed as unskilled manual labours, while 80 per cent of migrants leaving Ireland in 1881 described themselves as labourers, with 84 per cent of women describing themselves as domestic servants. Working in these spheres of employment, the Liverpool Irish were likely to have been more susceptible to the impact of trade depression, unemployment and poverty. In the words of Cox, Marland and York, ‘the portrayal of the Irish as able to take on the jobs no one else wanted, to survive on very little, and to inhabit the most squalid areas of town, resonates with accounts of Irish asylum patients’. Once their limited resources were withdrawn, Irish migrants appear to have been very vulnerable to mental breakdown.

Further reading:

Catherine Cox, Hilary Marland and Sarah York, ‘Emaciated, Exhausted, and Excited: The Bodies and Minds of the Irish in Late Nineteenth-Century Lancashire Asylums’, Journal of Social History, 46:2, (2012), 500-24.

W. J. Lowe, The Irish in Mid-Victorian Lancashire: The Shaping of a Working-Class Community (Peter Lang, 1989).

Donald MacRaild, The Irish in Britain, 1800-1914 (Dundalk (Studies in Irish Economic and Social History), 2006).