Framework and Background

The global has become the dominant paradigm of the social sciences and historical enquiry during the past ten years. Historians are now asking just how unique, how distinctive, is our current condition of an intense interlinking of economies and polities, and we are re-thinking our histories in relation to those of others in the wider world. Braudel first set a framework for thinking about Europe and the wider world in the projects of the Annales School. Global history has returned to those early aspirations, but has taken these in new directions. Global history started during the past ten years with a focus on large scale ecological change, on paradigms of ‘divergence’ and ‘convergence’, or on world networks of trade, capital and peoples. Books such as David Landes’s Wealth and Poverty of Nations and Eric Jones’s The European Miracle threw down the gauntlet of European exceptionalism. Answered by Asia-centred studies such as Ken Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence and Andre Gunder Frank’s Re-Orient, new global frameworks for analysing the roots of industrialization became key questions for the beginning of the Twenty-first Century.

That global agenda for historians has now extended far beyond those fundamental economic issues. History and social theory now focus on concepts of ‘connectedness’ or ‘cosmopolitanism’, of ‘entanglement’ and even ‘ecumenae’; in so doing we seek to identify and assess those connections that impacted on Europe’s and Asia’s cultures and development. But ‘global’ has also become a brand, and it is in danger of losing the vigour of the big questions with which it challenged the postmodernist perspective of the last decade.

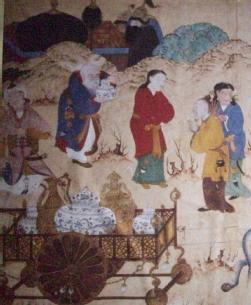

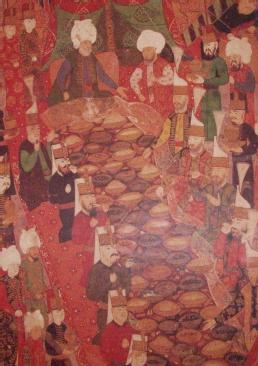

‘Europe’s Asian Centuries’ will return to those big questions by addressing the part played by mercantile trade with Asia in the origins of the Industrial Revolution. It will certainly engage with those new perspectives on global connections between Asia and Europe, but it will do so by investigating the products traded, how they were made, marketed and distributed in Asia, en route from Asia and in Europe. It moves the subject beyond the economics of trade flows and the politics of colonial domination to analyse the exchange of material culture and the transmission of knowledge, including that of skills, design and materials. It brings together the study of trade, of consumption and of production. It draws on transnational histories of ideas and material culture, and it sets these alongside the economic histories of different development paths.

The current history of the world economy (whether in recent years of boom or now in recession) is one of China’s and India’s economic ascendance. Europeans’ anxieties about their economic place in the world make it a priority for us to understand the long history of Europe’s connections with Asia. Issues now raised by world recession open new questions about the location of global manufacturing and the fates or prospects of industrial workforces. We cannot now write our histories of Europe’s industrialization without understanding both the extended comparative history of Asia’s economic growth, and the long history of connections between these regions of the world.

The global agendas of my study challenge the established divide between Europe and Asia in our history writing. Its methodological agendas challenge another great divide between economic history on the one hand and cultural and social history on the other. Economic histories of early modern Europe and its colonial empires are still separated off from social and cultural histories of consumption and material cultures. Jan de Vries set out to unite these histories in his concept of the ‘industrious revolution’. His pan-European study connected household behaviour with macro-economic labour and capital markets. De Vries opened the gates of economic history to questions of consumer desire, taste and sentiment that changed households and fostered incentives to large-scale productivity growth. He also linked consumer cultures in Europe to encounters with wider-world material cultures. It is now time to pursue the possibilities he opened up; to connect up those divided histories, to work at the interface of those histories of consumer and material cultures and the big questions asked by economic historians.

Study of consumption, production and world trade must also face another divide: the divide of area studies and of the barriers of imperial, and new imperial histories. The studies we have of world commodity trade lie mainly within the traditional imperial and colonial histories; new imperial histories have focussed on representations and texts, the discourses of empire. With these disjunctures we have also lost the issues which allowed historians to speak across the borderlands of Europe and Asia.

It is time to reinstate these issues by turning to the study of trade and exchange of material cultures. Trade has been analysed as quantitative flows, as commodity chains and as colonial power. Material cultures, in contrast, until recently have been the domain of the museum and of art history. The large volumes of valuable research published in all of these separate areas and in different historiographical traditions across Europe and Asia make it possible now to bring these approaches together, to take stock and to integrate these findings with new global approaches and interdisciplinary methods.