Dr Gavin Schwartz-Leeper

The Centre for the Study of the Renaissance, the Humanities Research Centre, and the Newberry Library were kind enough to award me the 2015 Warwick Transatlantic Fellowship to undertake foundational research on my new project, ‘The Art of Richard Grafton: The Cultural Networks of a Mid-Tudor Printer’. Richard Grafton (c.1511-1573) was the royal printer to Edward VI, sometime Member of Parliament for London and our own Coventry, and a master of the Grocers’ Company. He played a seminal role in the production of the first printed English Bibles, was imprisoned several times for printing materials insensitive to the contemporary political and religious climates—for example, printing a proclamation declaring Lady Jane Grey queen—and engaged in one of the greatest historiographical feuds of the early modern period with renowned chronicler and antiquary John Stow, fundamentally shifting how contemporary England viewed its own history (and thus how we understand English history even today). He was father-in-law to Richard Tottell, the printer of the first (printed) collection of the poetry of Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, earl of Surrey, and he played a key role in setting up the royal hospitals in London.

Yet for all that, Grafton has largely been overlooked in favor of figures like John Stow—whose Survey of London has been at the center of fascinating research projects like the Early Modern Map of London—or Raphael Holinshed, whose massive Chronicles have recently been edited and published online. This is perhaps understandable: Grafton’s outputs are less sensational than John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, for example, which also has appeared in a new online edition, and therefore attract less interest. Where Grafton’s work has been considered, scholars have confined themselves to his most famous productions: chiefly, his expansion of Edward Hall’s Union of the two noble and illustre houses of York and Lancaster (also known as Hall’s Chronicle), his own Chronicle at Large, and his edition of John Hardyng’s Chronicle. This focus on Grafton and chronicling has had a distorting effect on our understanding of Grafton’s intellectual and economic interests; more importantly, it has warped how we view printers in the period. Grafton did not only print histories: these were simply texts that he appropriated and adapted alongside a range of others, like virtually every other early modern printer. The strongly Protestant character of these histories has also helped obscure the transnational nature of early modern print cultures.

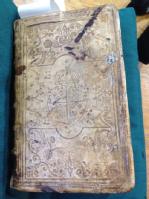

This Fellowship offered me the opportunity to attend a Newberry symposium on Renaissance print cultures in honor of the 500th anniversary of the death of Aldus Manutius, the Venetian printer whose development of italic type and the octavo handbook helped bring printed texts out of the libraries and into the everyday lives of readers. These features spread quickly across Europe via printer networks and demonstrate aptly how intellectual and economic print cultures were intertwined. I was also able to examine a range of texts produced by Grafton, Tottell, and Stow held at the Newberry, including a Matthew Bible (1537), a Great Bible (1539), several editions of Hardyng’s Chronicle (1543), and a range of editions and abridgements of Grafton’s Chronicle at Large (1569). The Newberry’s substantial collection allowed me to compare Grafton’s source-texts and original works, printing practices, and reader reception (via marginalia) to begin to piece together the broader contexts of Grafton’s printing networks. One of the highlights of the Newberry’s collection of Grafton’s printed texts is the 1552 edition of Thomas Wilson’s The Rule of Reason: while the text is notable in giving us the first reference to Ralph Roister Doister, the Newberry’s luxuriously-bound example belonged to Queen Elizabeth I.

Following on from this Fellowship, I am organizing a workshop on transnational cultures of knowledge in early modern print networks, to take place in early 2016. This workshop will utilize the strengths of the CSR along with our colleagues at Monash University in Melbourne via the Monash-Warwick Alliance.

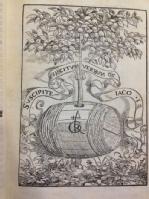

Fig. 1: Richard Grafton’s colophon, featuring a ‘tun’ for transporting books and a fruit tree with grafted branches.

Fig. 2: Elizabeth I’s personal copy of Thomas Wilson’s The Rule of Reason (printed by Grafton in 1552).