Dispatch One: Looking For the Left in San Francisco

Janelle Reinelt

August 9, 2017

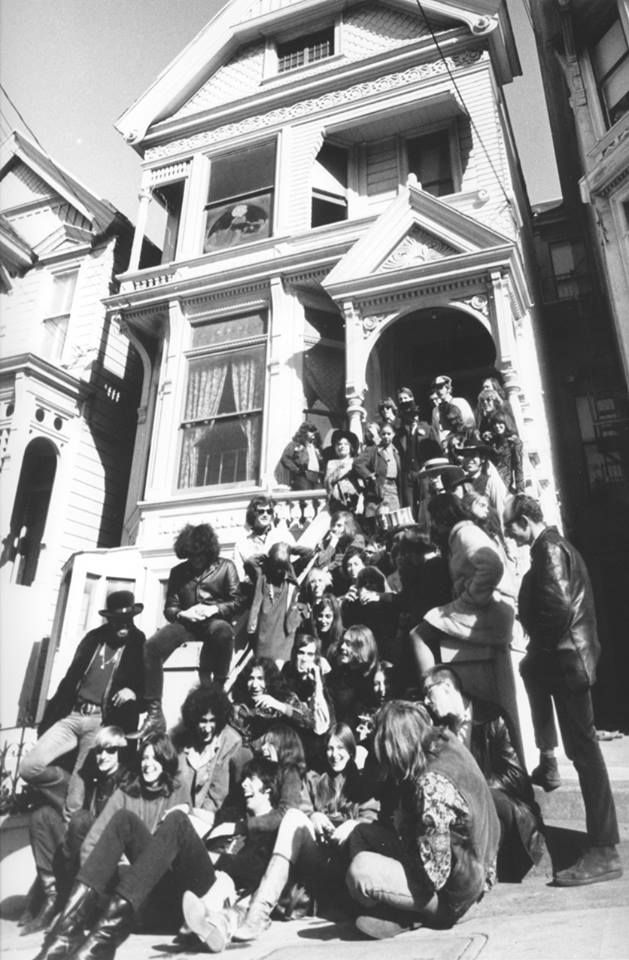

Fifty years ago, 100,000 young people converged on a neighborhood in San Francisco known as Haight Ashbury, named for the streets’ intersection at the center of the scene. Teens came from all over the United States, drawn by news of a utopian movement that was setting up an alternative way of life driven by notions of ‘peace’ ‘love’ and ‘freedom’ by people called ‘Hippies’, a word that carried connections to an earlier Beat movement that was ‘hip’ and presaged a technological future in Silicon Valley when ‘hippies’ would transform into ‘hipsters’. This playful etymology seeks to align seemingly disparate strands of cultural practice, joined by the geographic location of the ‘Bay Area’ in California, a place that since the Gold Rush in 1849 has been a crossroads of struggle and social aspiration. In 1967, this region formed a kind of epicenter for political, social, and artistic activity that defined the American sixties and the idea of the counter-culture. It was certainly deeply intertwined with Left politics and praxis, but this is by no means a simple or even obvious association: the ‘Summer of Love’ as it came to be called could be seen (and has been by many) as more about drugs, music, fashion, and pleasure than about forging a new way to live together that rejected consumerism, war, and inequality while embracing diversity, peace, and the environment.

During this current summer (2017) a number of exhibitions, performances, concerts, and other events have commemorated the ‘Summer of Love’. Inevitably, differently inflected narratives put the emphasis on different parts of this story, creating multiple histories that sometimes clash. I attended four events in Berkeley and San Francisco, seeking to understand what part of this history might be considered Left, and what legacy it might offer to a present time calling out for political vision and renewal. In three ‘dispatches’ appearing in coming weeks, I hope to report from a California location which is still vibrant, criss-crossed with contradictions, and, in the Trump era, is shaping up to be a major flash point for political issues such as immigration and free speech.

Performance, of course, is all over this region’s history. The Actor’s Workshop, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Julian Theatre, the Committee, and an anarchist collective called the Diggers were creating and performing in 1967 (soon to be followed by Teatro Campesino). While these groups were ‘doing theatre’, they were also building community, resisting injustice, forging alliances with other groups and making common cause with a number of protest efforts, such as opposition to the Viet Nam war. Theatre was everywhere, but it has often been overlooked or underplayed in narratives that emphasize instead the extraordinary music of this period and the major bay area musical figures from Joan Baez to the Grateful Dead, folk music to psychedelic rock. In the exhibits I attended, however, one could find the connections to the performance groups and see how they interacted with other public practices such as marches and demonstrations. Sometimes, when this history was buried, it could be excavated from the archives presented.

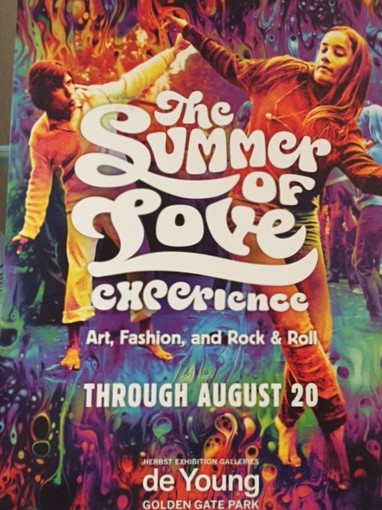

The biggest and most high-profile exhibit about the Summer of Love was staged at the de Young Museum, San Francisco’s fine arts museum founded in 1895. The de Young showcases American art from the 17th through the 21st centuries, international contemporary art, textiles, and costumes, and art from the Americas, the Pacific and Africa. The exhibit title plays to this strength: ‘The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion and Rock & Roll’. I’ll describe some of my impressions of the artifacts and their curation by highlighting certain sequences of display. In a short blog, there is no way to give a comprehensive account of this large exhibit of over 300 objects, so it should be said that my account is also a kind of curation, since I will only highlight what was important to me and to our Culture(s) of the Left project.

Entering and First Impressions

The museum is situated within Golden Gate Park, a large iconic public park of over 1000 acres which holds the museum, the Academy of Science, the Botantical Gardens, a Japanese Tea Garden, and the National AIDS Memorial Grove. It also has an area designated ‘Hippie Hill’ because it became a gathering space for early hippie culture, close to Haight St. As I walked up Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive toward the museum, the first thing I noticed was the display of cross-street signs lining the approach. Of course, Haight/Ashbury was the first among these signs, but the rest referenced only virtual streets: Hippie/Hipster, Civil Rights/Black Lives Matter, Whole Earth Catalogue/World Wide Web. Immediately, this first display drew attention to the historical intersection of then and now (the first term from the 60s, the second from the present) and it also put politics squarely in the center of any spectator’s frame. To come to this exhibit, one had to confront the present as well as the past.

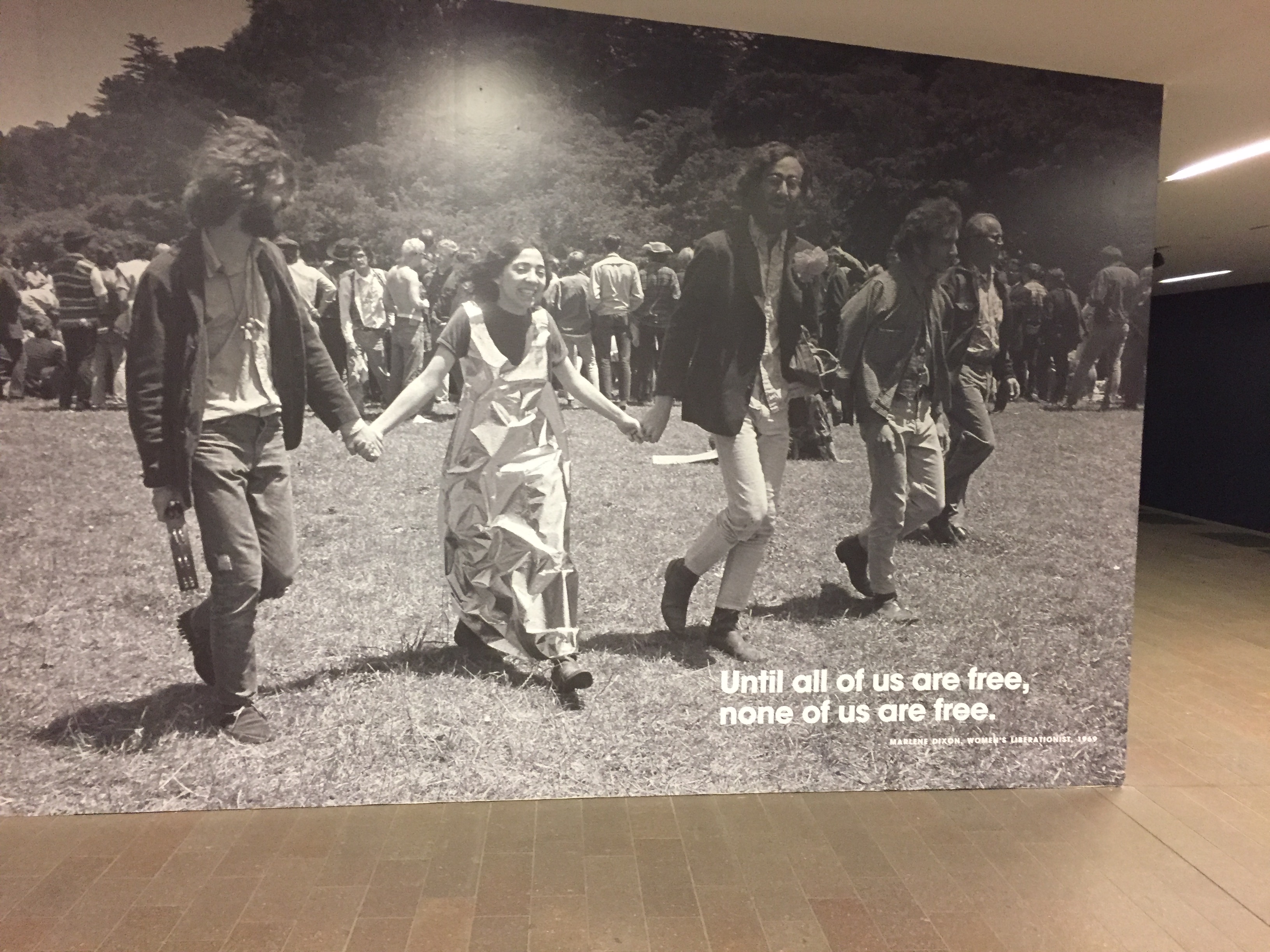

The waiting area and entrance to the exhibit were covered with 7 large wall mural photos of famous people and ordinary people, and information about how they fit into the timeframe and the region. For example, one wall showed Marlene Dixon, who became the leader of a militant ultra-left party called the Democratic Workers Party. In the photo from 1969, she was simply identified as a feminist and the accompanying text read, ‘Until All of Us are Free None of Us is Free’. Another featured a quotation from the Police Captain of the Park Street Station that oversaw the Haight: ‘They somehow got the idea that there would be free love, free pot, free food, and a free place to sleep’. This text was superimposed on an image of a large crowd of young people hanging out in the streets. These wall murals emphasized the public nature of the spectacle that was the Summer of Love and also the tension between participants and the state. Then governor of California Ronald Reagan is featured charging the actions of young people with ‘polluting the environment’, an especially ironic claim considering Reagan’s conservative stance on environmental regulation as both governor and President. As I walked into the exhibit proper, I was buoyed up by the promise of an exhibit that would focus on the important political issues that formed the context for the Summer of Love. However, I was to find that these early markers of what was at stake were quickly overtaken by the dominant themes presented here: drugs, rock ‘n roll, and fashion.

Drugs and Other Pastimes

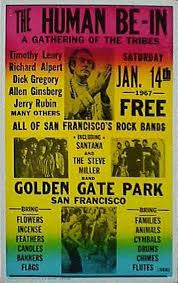

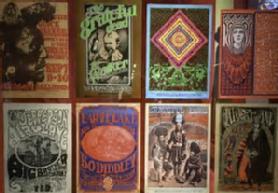

Until 1968, LSD was legal to produce and to use. Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), was one of a well-known group of San Franciscans who were regularly celebrating getting high. The Merry Pranksters threw parties called ‘Acid Tests’, attended by beat generation figures such as Allen Ginsberg and LSD advocate Timothy Leary. The Grateful Dead, Kesey’s favorite band, was often on hand. In 1966, one of the Pranksters, Stuart Brand, who later published the Whole Earth Catalog, organized the Trips Festival at the Longshoremen’s Hall. The Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company played, as did the Jefferson Airplane. 10,000 people attended over three days. There is a sizeable recognition of this event in the de Young museum exhibit, although there is no mention of the connection to the Whole Earth Catalogue nor to the fact that the Longshoremen’s Hall was itself an important labor union site, and the Longshoremen had a history of radical resistance and left-wing politics, many members being affiliated with the Communist Party of America. In 1934 the West Coast Longshoremen’s Strike led to a general strike in San Francisco and the eventual unionization of all West Coast ports. These details about the venue for the Festival are important to know because they indicate the connections between labor and culture in the events of the 60s countercultural movement. Bay area longshoremen were active in the Anti-War Movement and other important causes in the period. The Trips Festival was represented in the exhibit by a poster for it, and it was surrounded by a series of posters showing the development of acid design in posters and other print media, and also by a demonstration of a light show (the Trip Festival featured one of the first full-blown light shows of the era). The important connections to environmental concerns and labor politics dropped out of the picture unless one already knew about them.

Along with a large amount of poster art, the de Young chose to exhibit a number of fashion designs and hand-made garments featuring ‘hippie’ effects such as macramé, quilting techniques, crochet and knitted clothing. While the curation did not provide a discussion of the value of hand-made garments or traditional techniques such as quilting and needlework, it did include one important notation: In 1966 85% of women and girls in the US could sew. They were not necessarily rebelling through the new fashions since they were at the same time continuing and handing on traditions often learned from parents and grandparents. There is a complex story to be told about fashion, from the revealing near-nude effects of some designs to the very complete and ‘buttoned up’ styles favored by others. However, the exhibit had no appreciable comment on these complexities. In the last room of the exhibit, a pair of jeans embroidered and embellished held focus in the center display case. On the seat of the pants, a Nixon cartoon was appliqued in the center. This comical anti-war protest against Nixon shows how some political messages got into the fashion designs. Still, the fashion portions of the exhibit were more or less simply a collection of clothes and ‘looks’ of the period without contextual social history.

Theatre in the Streets (and Parks)

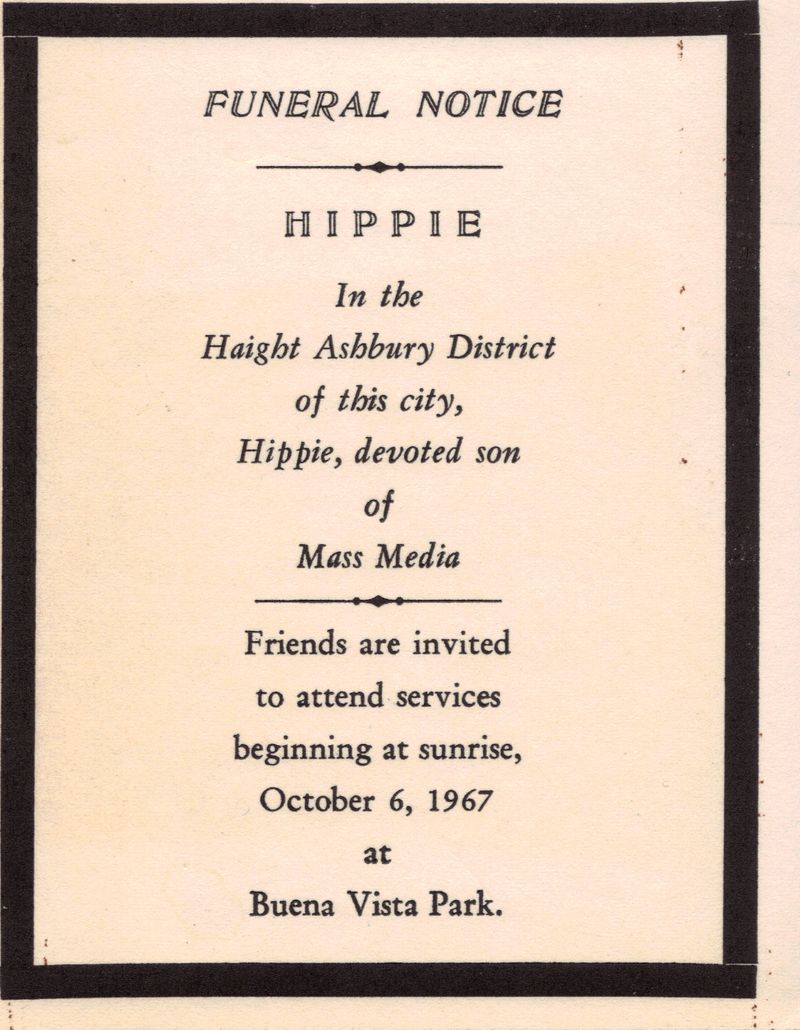

Looking for traces of performance, the most important room (to me) in the exhibit was one which had a lot of photos and memorabilia from the Haight Ashbury neighborhood and its infusion of young people during the Summer of Love. Documentation presented large numbers of people on the streets, wearing interesting costumes, smoking weed, perhaps dancing alone or with others. The ‘Be-In’ of the previous January is represented in a number of photographs and posters. My eyes were drawn above all to a portion of a wall given to the Haight Ashbury neighborhood Free Clinic and Free Store, enterprises of the Diggers, who were basically a theatrical group. They lived in the Haight, and were involved in everything important happening there, from the neighborhood newspaper, The Oracle, to other efforts such as the 75 free turkeys they provided for the Be-In to feed people. They were an anarchist, anti-capitalist group who thought money was the root of a lot of evil, and that real freedom meant lots of free things. At the Free Store, people could come in and take what they wanted (donated things like blankets or sleeping bags, or used clothing). The Free Clinic started when the Diggers contacted the young doctors at the University of California Medical Center and got some to volunteer to run the clinic one night a week, sometimes more. A flier for an evening clinic is displayed that makes it clear what some of the issues were—‘how to avoid getting raped, getting STDs or pregnant’; how to handle drug overdoses; how to fight infection on the street. The Diggers also offered free performances, and staged a ‘Death of Money’ happening in which funeral pall bearers wore animal masks and sang The Supreme’s ‘Get Out of My Life, Why Don’t You Babe’. They also protested the hyped media coverage of the Summer of Love and the absorption of the Hippies into commercial culture in the performance, ‘Death of Hippie, Birth of Free’. Finally, on one of the walls, a community message board from the Free Clinic sported humorous messages such as ‘Feed Your Head’, but also a call for a clean-up day that read, ‘We the hippies of the Haight want to clean up our place’.

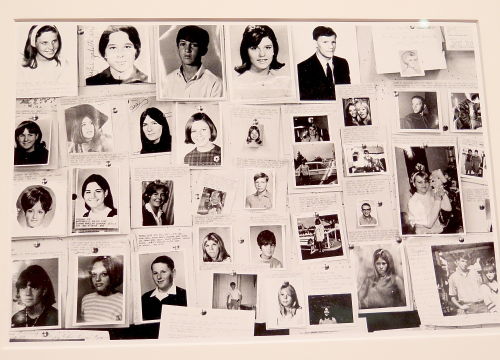

One other artifact in that room moved me as well: A bulletin board from the Park Street Police Station. About twenty-five photos of missing children were posted on the board, along with notes from parents and relatives who were trying to find them and had contacted the local police. Those photos are revealing—from all over the country, teenagers left their homes and headed for San Francisco. They are very very young—14-17 in most cases. They stare out from the wall in their graduation clothes, hair slicked back, girls with ‘ratted’ hair in the style of the time, boys in suits and ties (probably graduation or church clothes). It is important to acknowledge these young people and to know that some of them were never found. The other day as I drove along in my car listening to the radio, I happened on an interview on National Public Radio with one of those young girls whose picture was on the wall. Someone attending the de Young exhibit recognized her, carried out a on-line search, and found her living in Oregon. She is in her 70s, and reported that yes, she had run away from her east coast home because her parents were too conservative and she wanted a different life. She didn’t make it to San Francisco that summer because she ran out of money in Portland Oregon. But she found a job and a place to live, saved up her money, and came out to San Francisco the next summer. She considers herself one of the counter cultural generation, and does not regret anything in her life (she has several children and has been twice married). She reported that she got back in touch with her parents eventually, and looked after them at the end of their lives. I found her story touching; it affirmed some of the better aspects of the Summer of Love story.

Overall, the de Young Summer of Love exhibit disappointed me because it seemed to be addressing a middle-of-the road spectator, not emphasizing the political conflicts, and not taking any strong positions on the movements. In my next blog, I’ll write about two other exhibits at the California Historical Society and the Berkeley Art Center that put the protest aspects of these times more squarely in the center of the displays, and with them, curation that provided historical and social context for the photos and artifacts, tying the past into the present in an activist mode of exhibiting their content.

Postscript 11 September 2017

I woke up to find the San Francisco Chronicle, my morning paper, reporting that the San Francisco Travel Association won a prestigious award for the best integrated marketing campaign and branding for the Summer of Love, given by the US Travel Destinations Council. Apparently, estimated ‘global media impressions’ (the number of times people worldwide were made aware of this campaign) numbered 3.475 billion. As so often with this kind of thing, I can’t decide if I am more pleased at the widespread attention or more appalled at the neoliberal global capitalism that underpinned the whole thing.