What is global leadership?

See our new book: Developing Global Leaders: Insights from African Case Studies. Eva Jordans, Bettina Ng'weno and Helen Spencer-Oatey. Published by Palgrave Macmillan, January 2020.

Leadership is notoriously difficult to define. Over 40 years ago, Ralph Stogdill (1974) argued that “there are almost as many different definitions of leadership as there are persons who have attempted to define the concept” (p. 7). Gary Yukl (2013), in his well-known book on leadership in organisations, recently argued along the same lines. Nevertheless, people continue to put forward definitions and here are a few:

Definitions of leaders and leadership

“Leadership is an activity or set of activities, observable to others, that occurs in a group, organization or institution, and which involves a leader and followers who willingly subscribe to common purposes and work together to achieve them.” (Clark & Clark, 1996, p. 25)

“Leadership is not a person or a position. It is a complex moral relationship between people based in trust, obligation, commitment, and a shared vision of the good.” (Ciulla, 2014, p. xv)

“Leaders need to shape the future, get things done, manage others, invest in others, and demonstrate personal proficiency.” (Ulrich & Smallwood, 2012, p. 32)

“Leaders determine or clarify goals for a group of individuals and bring together the energies of members of that group to accomplish these goals.” (Keohane, 2014, p. 152)

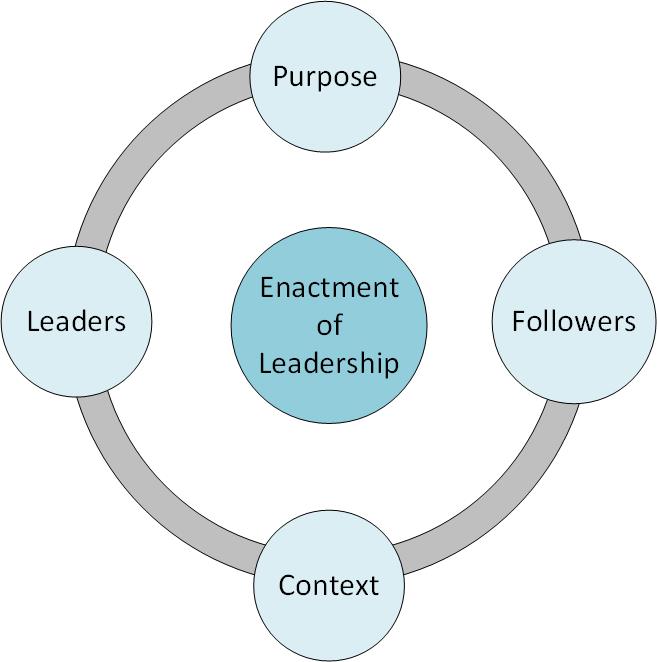

One way of making sense of the numerous definitions of leaders and leadership is to build on the definition given by Clark and Clark (1996). As can be seen, they identify leadership as an activity or process that has a number of interconnected elements: a leader and followers, who work in a particular organisation or context and have a common purpose or aim. In this view, leadership is not simply the behaviour or qualities of the person in charge (i.e. the leader); rather it is the enactment of a complex and dynamic interaction of four key elements, as shown in the figure to the right. We call this the leadership multiplex. (See the diagram on the top right of this page.)

Focus on the leader

A very large proportion of the literature on leadership has focused on the person of the leader, seeking to identify the characteristics of ‘great leaders’. This is typically done through studying and/or interviewing (highly) successful leaders and identifying their traits, characteristics and/or behaviours, in the hope of specifying the ‘key ingredients’ of a successful leader.

Bird (2013) reports that over 150 different competencies have been associated with global leadership effectiveness, and a study by the Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership (2002) lists an even larger number of leadership competencies. This is clearly far too large a number for ease of handling, especially in terms of leadership development, and so he has proposed a smaller set of core competencies, divided into three categories. These are shown in the table below.

|

Managing Self |

Managing People & Relationships |

Business and Organizational Acumen |

|

1. Inquisitiveness 2. Global mindset 3. Flexibility 4. Character 5. Resilience |

6. Valuing people 7. Cross-cultural communication 8. Interpersonal skills 9. Teaming skills 10. Empowering others |

11. Vision & strategic thinking 12. Leading change 13. Business savvy 14. Organizational savvy 15. Managing communities |

Managing self

‘Management of self’ is a key facet of effective leadership. Our diagnostic tool, the Global Professionals Profiler (GPP), helps participants identify their relative strengths and weaknesses, and all three of our GlobalPeople@Work e-modules, in combination with the live workshops, help participants enhance their personal qualities and strengths.

Managing people and relationships

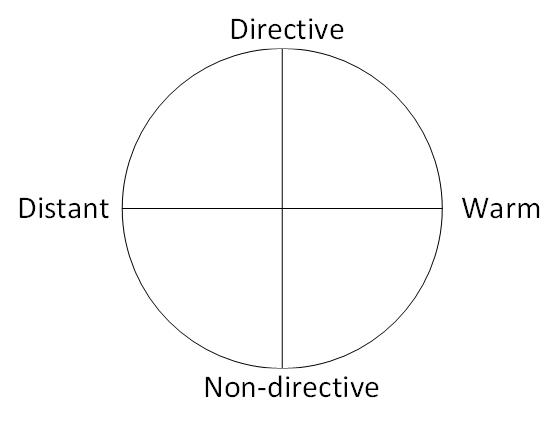

Leadership ‘success’ is not dependent only on the leader – it is hugely influenced by the dynamic of leader–follower relations. In other words, the nature of leader–follower relations is an extremely important aspect of the leadership multiplex. Two frameworks can be particularly helpful for this: rapport management (covered in the e-course Global Leaders@Work) and the leadership circumplex.

Research in psychology (e.g. Acton & Revelle, 2002; Wiggins, 1979) has shown that interpersonal interactions are best summarised by two main dimensions, agency and affiliation. The scale ends of these dimensions have been variously named as follows:

- Dimension 1: Agency: Control/dominance/authority vs. flexibility/submission/disengaged

- Dimension 2: Affiliation: Warm/friendly/trusting vs. cold/hostile/distrustful

(See the diagram near the top right of this page.)

Redeker, de Fries, Rouckhout, Vermeren, and Filip (2014) have applied this to leadership, proposing a number of different leadership styles, depending on people’s preferences relative to the two dimensions. Are some styles better than others then? In our view, there is no one style that is always better than another. This is because the nature of the relationship between leaders and followers is to a large extent dependent on everyone’s expectations of leadership. If the expectations of leader and follower are compatible, then everyone may feel satisfied, but if leaders and followers hold differing expectations, then tensions and dissatisfaction are likely to arise. For example, if followers want and expect their leader to give clear instructions, and this is what the leader does, then their respective expectations match and all is well. On the other hand, if the followers want and expect their leader to give clear instructions while the leader prefers a more participative style, both parties may be dissatisfied. As Molinsky (2013, pp. 6-7) illustrates with an authentic story of an American manager in India, the followers may interpret the lack of instructions from their boss as evidence of incompetence, while the leader may judge the followers as not showing enough initiative. A similar mismatch of expectations is evident in several of our case studies, especially between young and senior leaders.

In our e-module, Global Leaders@Work we explain this way of considering leadership.

Global leadership

Up to now in this article we have not distinguished between leadership and global leadership. What then is the difference? Caligiuri (2006, p. 220) identifies ten tasks that she found to be common among – or unique to – people in global leadership positions:

- Global leaders work with colleagues from other countries.

- Global leaders interact with external clients from other countries.

- Global leaders interact with internal clients from other countries.

- Global leaders may need to speak in a language other than their mother tongue at work.

- Global leaders supervise employees who are of different nationalities.

- Global leaders develop a strategic business plan on a worldwide basis for their unit.

- Global leaders manage a budget on a worldwide basis for their unit.

- Global leaders negotiate in other countries or with people from other countries.

- Global leaders manage foreign suppliers or vendors.

- Global leaders manage risk on a worldwide basis for their unit.

Even a cursory glance at this list shows that ‘global’ is equated with ‘national difference’ and, in one case, with language differences. Yet this may be too narrow an interpretation. Cabrera (2012), past president of Thunderbird School of Global Management, comments as follows:

Truly global leaders act as bridge builders, connectors of resources and talent across cultural and political boundaries. … The global mindset allows leaders to connect with individuals and organizations across boundaries.

In a similar vein, the World Economic Forum, in relation to their Global Leadership Fellowship programme, describe global leaders as follows, also linking it with systems leadership:

dynamic, engaged and driven individuals who possess a high degree of intellectual curiosity and service-oriented humility; an entrepreneur in the global public interest with a profound sense of purpose regardless of the scale and scope of the challenge.

Systems leadership is about cultivating a shared vision for change - working together with all stakeholders of global society. It’s about empowering widespread innovation and action based on mutual accountability and collaboration.

These descriptions make it clear that global leadership entails connecting across a wide range of boundaries, not just national and linguistic ones. There are all kinds of boundaries in the workplace (and beyond) that people need to work across, such as age, religious belief, professional group, and so on, and all these various boundaries can affect interaction and the leadership multiplex. This is because different cultural groupings, whatever their size, can have their own cultural practices and perspectives, which can give rise to different expectations and evaluative judgements. Sometimes smaller groups are nested within larger groups (e.g. a department within an organisation), but sometimes smaller groups may cut across larger groups (e.g. a team may be made up of people from different departments). Moreover, individual people can be members of multiple groups, with different individuals showing different membership constellations. In addition, of course, individuals have their own personal characteristics, such as personalities, senses of identity, personal histories and so on.

Recent theorising on leadership, diverse teams and the issue of boundaries has led to the development of a particularly useful theory: faultline theory. This theory helps explain why sharp boundaries or faultlines may appear among staff members and what leaders can do about it. Gratton, Voigt, and Erickson (2007, p. 25) offer the following overview:

In the geological analogy to faultlines, various external factors (such as pressure) have an impact on how a fault actually fractures. … Strong faultlines emerge in a team when there are a few fairly homogeneous subgroups that are able to identify themselves. … Strong faultlines can create a fracture in the social fabric of the team. This fracture can become a source of tension and a barrier to the creation of trust and goodwill and to the exchange of knowledge and information.

In our e-module, Global Teams@Work, we explain the concept of faultlines, its importance for understanding teamwork, and ways of handling it.

Other important facets of global leadership

There are a number of other aspects of ‘global working’ that are important for global leadership and working in global teams, including communication, attitudes to time, and the balancing of task and relationship priorities. These are all explored in the component modules of our e-course, Global People@Work. They are also probed in our diagnostic/needs analysis tool, the Global Professionals Profiler (GPP).

Acknowledgement

This article is based on the following chapter:

Spencer-Oatey, Helen (2020) Global Leadership: Key Concepts and Frameworks, in E.Jordans, B. Ng’weno and H. Spencer-Oatey, Developing Global Leaders: Insights from African Case Studies, Palgrave.

References

Acton, G. S., & Revelle, W. (2002). Interpersonal personality measures show circumplex structure based on new psychometric criteria. Journal of Personality Assessment, 79(3), 446–471.

Bird, A. (2013). Mapping the content domain of global leadership competencies. In M. E. Mendenhall, J. S. Osland, A. Bird, G. R. Oddou, & M. Maznevski (Eds.), Global Leadership: Research, Practice and Development (pp. 80–96). New Yokr: Routledge.

Cabrera, Á. (2012). What being global really means. Harvard Business Reivew. International Business. Available at https://hbr.org/2012/04/what-being-global-really-means.

Caligiuri, P. (2006). Developing global leaders. Human Resource Management Review, 16(2), 219–228.

Ciulla, J. B. (Ed.) (2014). Ethics, the Heart of Leadership. 3rd ed. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

Clark, K. E., & Clark, M. B. (1996). Choosing to Lead. 2nd ed. Greensboro, North Carolina: Center for Creative Leadership.

Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership. (2002). Managers and leaders: raising our game: Centre for Excellence in Management and Leadership, available at https://www.bam.ac.uk/sites/bam.ac.uk/files/CEML%20Final%20Report.pdf.

Gratton, L., Voigt, A., & Erickson, T. (2007). Bridging faultlines in diverse teams. MIT Sloan Management Review, 48(4), 21–29.

Keohane, N. O. (2014). Democratic leadership and dirty hands. In J. B. Ciulla (Ed.), Ethics, the Heart of Leadership, 3rd ed. (pp. 151–175). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

Molinsky, A. (2013). Global Dexterity. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Redeker, M., de Fries, R. E., Rouckhout, D., Vermeren, P., & Filip, d. F. (2014). Integrating leadership: the leadership circumplex. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(3), 435–455.

Ulrich, D., & Smallwood, N. (2012). What is leadership. In W. H. Mobley, Y. Wang, & M. Li (Eds.), Advances in Global Leadership, Vol.7 (pp. 9–36). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(3), 395–412.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in Organizations. 8th ed. Harlow, England: Pearson Education.

The Leadership Multiplex

The various interconnected facets of leadership that need managing

Interpersonal dimensions of Leadership

Leaders need to vary flexibly the emphases they give to the different ends of the two dimensions

Overview of findings

Overview of findings