Napoleon’s Last Stand: 100 Days in 100 Objects

An online exhibition, curated by the University of Warwick, will provide a new angle on the Battle of Waterloo, whose bicentennial anniversary is commemorated this year.

Everybody knows about Waterloo, of course, but fewer people know that Napoleon had already been defeated and exiled one year earlier and that in a dramatic turn of events in February 1815, escaped from Elba, raised an army, and marched on Paris. Having toppled the newly restored monarchy, he reinstated the Empire – and only then faced the Allies at Waterloo in June.

Launching today, the exhibition will trace Napoleon’s return and defeat by releasing one object for each day of the period known as the ‘100 Days’. The exhibits have been selected by an international array of Napoleonic scholars and museums, and are curated by a team at the University of Warwick.

Dr Kate Astbury, of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Warwick said: “We wanted to put the Battle of Waterloo into context, and move away from the traditional British focus on the ‘duel’ between Napoleon and Wellington.

“Our objects highlight the reaction of ordinary individuals – as well as public figures – from across Europe to the renewed political uncertainty and military conflict. The exhibition will contain everything from the personal and quirky to items of national importance, with several objects coming from private collections and archives not open to the public.”

Professor Mark Philp from the University of Warwick History Department added: “We hope what we’ve provided is a nuanced, broader picture of the events leading to the Battle of Waterloo and the ramifications of these events on the political landscape.

“Whereas by 1814, most of Europe thought the radicalism of the French Revolution had finally been contained, the 100 Days showed that a monarchy couldn’t simply be restored by European alliance as if nothing had happened.

“When Napoleon escaped from Elba and landed in France in February 1815, he did so by presenting himself not as an autocrat, but as a popular hero: he could, as Balzac later put it, ‘gain an empire simply by showing his hat’! By moving beyond the largely military terms of the usual discussion of 1815, this exhibition draws attention both to civilian and popular responses to this dramatic period, and its implications for the political landscape of Europe.”

The online exhibition goes live today, Monday 23 February and there's also a sneak preview of items to come here.

Exhibits will include:

- A purse owned by Kitty Wellington, which draws attention to the hurried flight of French royalists and foreigners alike from Paris, fearing conflict and reprisals as Napoleon approached.

- German, Dutch and Italian prints, which demonise Napoleon as a bloodthirsty tyrant and a threat to the security of Europe.

- Le royaliste converti, a short theatrical sketch performed in Paris on 12 April 1815, which uses songs to dramatise a Bonapartist converting a royalist to ‘true French patriotism’ – indicating the persistent popularity of Napoleon, in some quarters at least.

- A ticket to the plebiscite of the ‘Champ du Mai’ in June, at which Napoleon sought approval for his additions to the French constitution, showing how he returned to the idea of republican political participation.

- Colonel Fabry’s telescope, which was handed to Napoleon for him to see the arrival of the Prussians at Waterloo.

- Various letters, whether between civilian women or government officials, which show the confusion caused by the slow and piecemeal circulation of news around Europe in this period.

- Napoleon’s letter of abdication, 22 June 1815, 4 days after Waterloo.

- A memento mori of one of those who died at Waterloo: the grieving widow had the damaged vertebra of her husband encased in silver and kept it with the bullet that killed him.

- English folk ballads, which reveal that Napoleon remained a popular and heroic figure despite being the vanquished enemy.

Notes for editors:

For more information, or to arrange an interview, please contact: Alison Rowan, Communications Manager, a.rowan@warwick.ac.uk or by telephone on 024 7615 0423 or 07876 218166

Images:

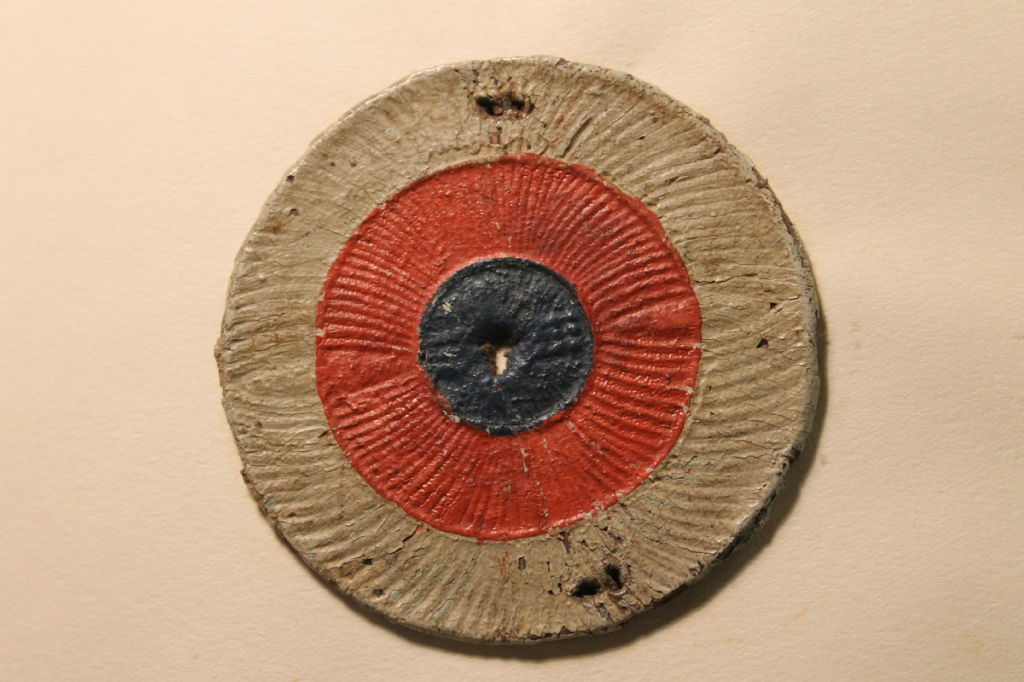

A cocade taken from a French soldier who died at Waterloo. The cockade comes from the Rose collection at the Bodleian.

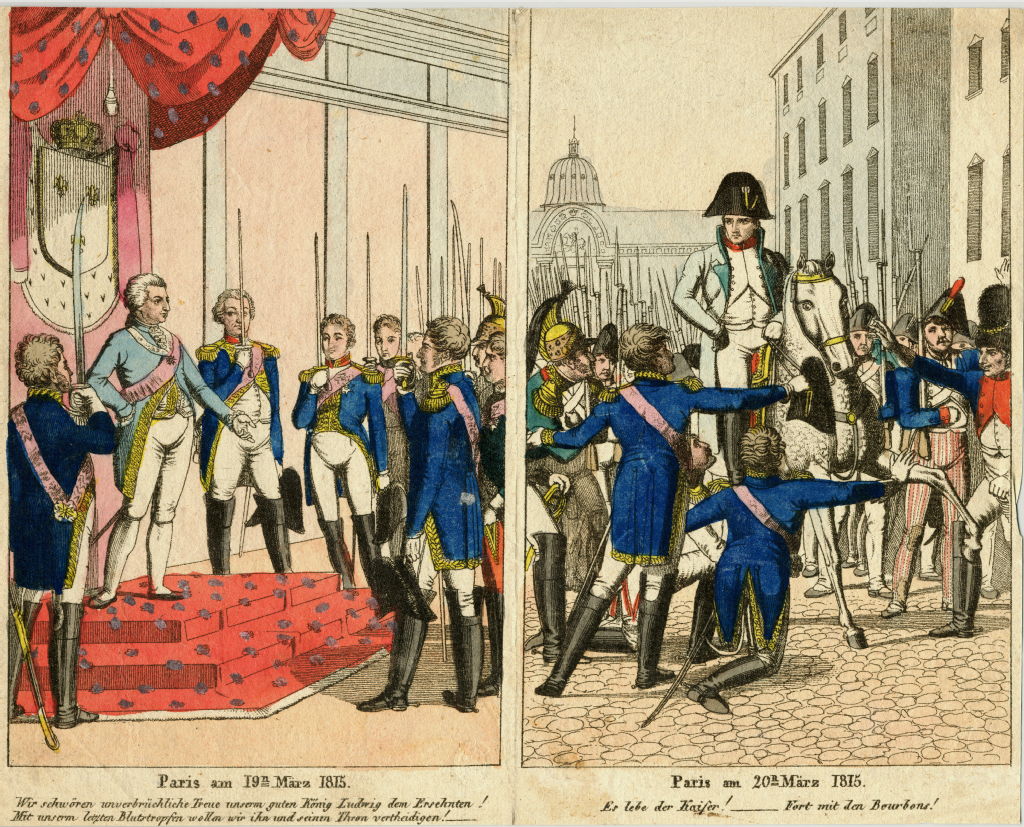

A print of Napoleon's return to Paris in March 1815, contrasting loyalty to the King one day with loyalty to Napoleon the next. The print is from the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig with many thanks to Christoph Kaufmann for the reproduction of the image and the rights to use it.